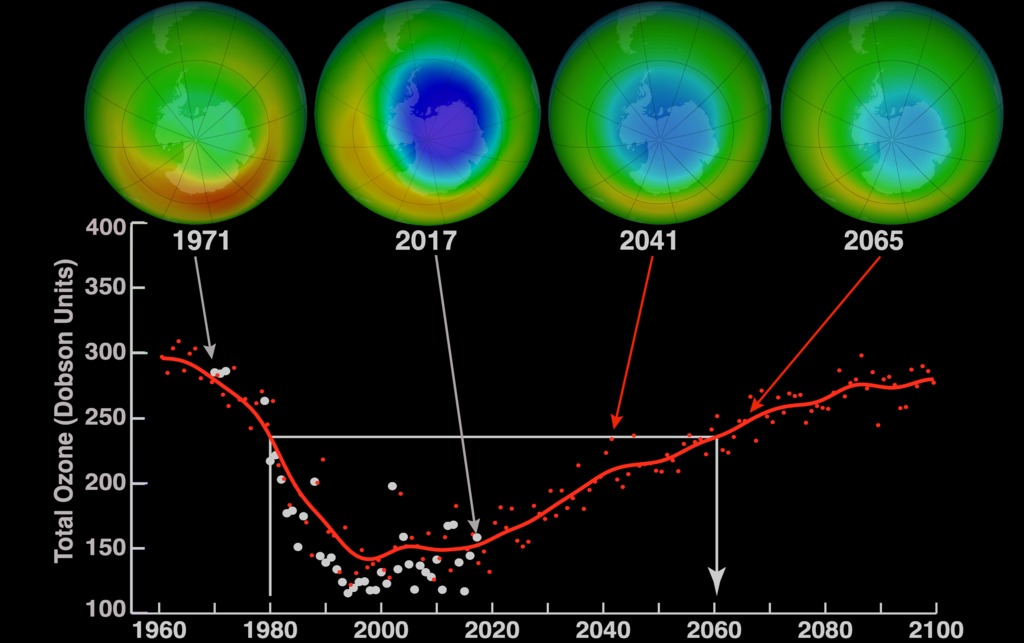

NASA reports of average minimum ozone in October over Antartica, and projections for the future.

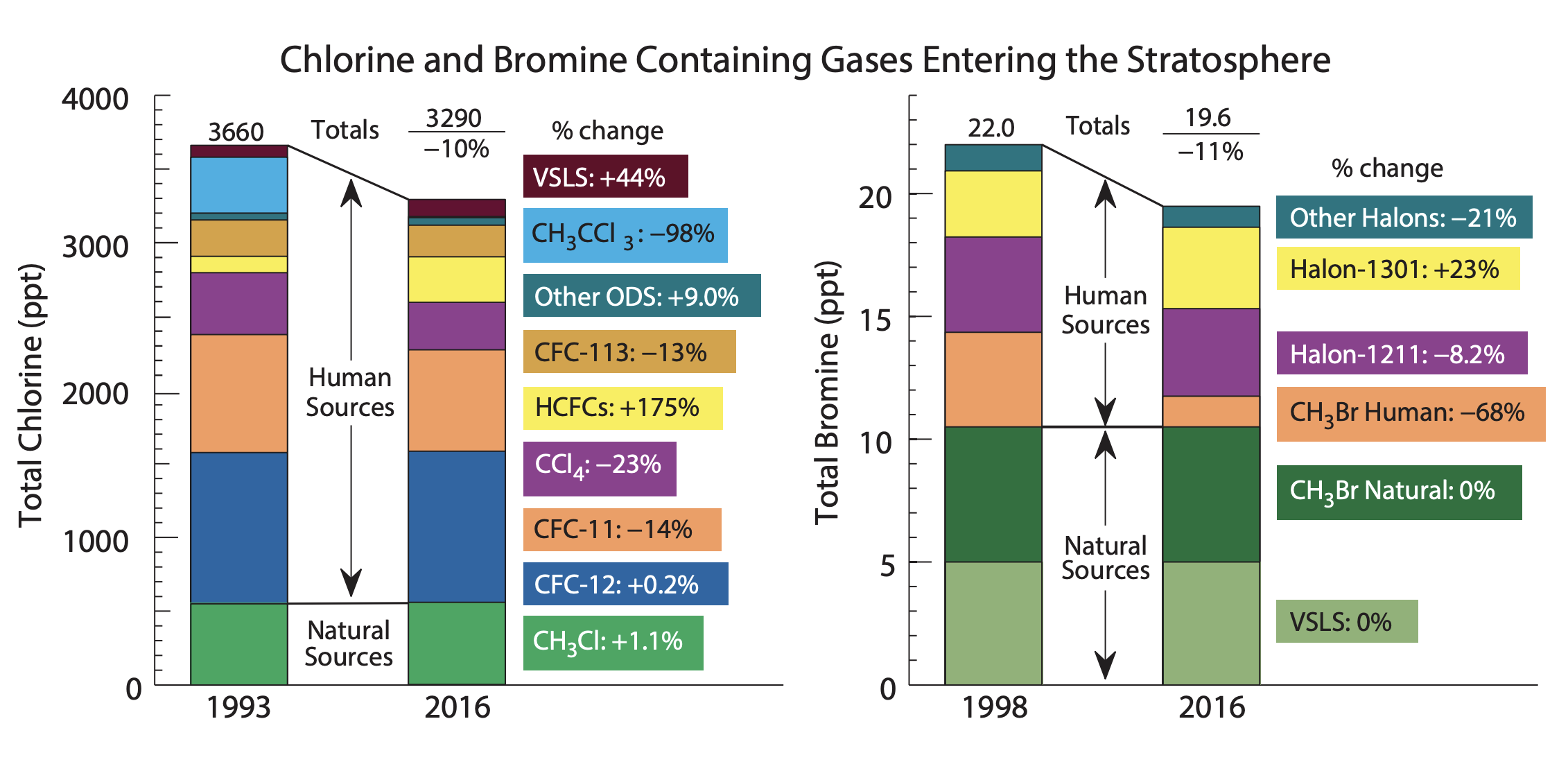

In 1987, the United Nations (UN) finalized the Montreal Protocol, a global agreement to heal the holes that had been growing in the ozone layer by reducing the use of certain chemicals, such as chlorine and bromine, found in aerosol cans, refrigeration systems, and the like. This week, the UN and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) published the Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion report, which had some startling good news: we are on our way to complete ozone layer repair!

Rapid Ozone Loss Spurs Fear

The ozone layer is a gaseous layer of the Earth's atmosphere that, like a layer of atmospheric sunscreen, soaks up harmful ultraviolet radiation from the sun, and helps capture the sun's warmth. Many of the same chemicals that deplete the ozone layer also contribute to global warming.

Part of what first made the ozone holes extremely disconcerting was the rapidity with which they appeared. It seemed as if this vital layer of the Earth's atmosphere could be gone within years. When the southern hemisphere hole was first discovered in 1985, ozone levels were compared to previous records and were found to be 35 percent lower than the average from the 1960s, and were lower than any records before 1983. The continued rapid growth of the holes sparked fear that the Earth would be bathed in high intensity uv radiation.

i

On the Mend

The new UN/WMO report says that the ozone holes in the northern hemisphere and at mid-latitude will be repaired in the 2030s, the holes in the southern hemisphere in the 2050s, and the polar regions in the 2060s. Much of this success is attributed to the Montreal Protocol, which mandated cuts in the use of certain chemicals that stopped the ozone from regenerating.

Figure ES-3 from the Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion showing the total amount of chlorine and bromine entering the stratosphere.

Cooperation at the Heart of the Montreal Protocol's Success

The Protocol is the first treaty to gain universal ratification from all countries in the world, and shows what can be done when governments work together to protect the environment. In 2016, the Kigali Amendment was adopted, furthering the commitment to the Montreal Protocol and additionally helping to keep global warming under the dangerous two-degree Celsius mark.

The Amendment goes into effect next year and is focused on further cutting the use of hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), man-made chemicals found in air conditioning, refrigeration systems, and foam insulation, among others. HFCs are potent greenhouse gasses that also destroy the ozone layer. By adopting and implementing the Kigali Agreement, thereby reducing the emissions of these destructive gases, we could prevent up to 0.5 degrees Celsius of global warming while continuing the repair of the ozone layer.

In a recent press release, Erik Solhein, head of UN Environment, said, "The Montreal Protocol is one of the most successful multilateral agreements in history… [and] the careful mix of authoritative science and collaborative action… is precisely why the Kigali Amendment holds such promise for climate action in future."

U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry delivers remarks during the conference about amending the Montreal ozone layer protection protocol held on October 14, 2016, in Kigali, Rwanda.

Planet Aid's Part

Helping to protect the environment is part of Planet Aid's mission. You can help us reduce greenhouse gas emissions, protect clean water, and save landfill space by donating your unwanted clothing and shoes in a yellow bin.

Keep up with other climate change news on our Climate Change blog series.