What Happens When Development Gets too "Pumped"

"We learned that doing work on the ground in Africa is hard and humbling work, even more so than anticipated." —Jean Case, The Case Foundation

Philanthropist Jean Case understands the myriad challenges of development work. Her blog "The Painful Acknowledgement of Coming Up Short" is a reflection on the failure of the now infamous PlayPump initiative. PlayPump is a merry-go-round driven pump that delivers water when children spin around on its colorful carousel. It received widespread attention after PBS Frontline aired a video in 2005 that applauded the pump's innovative virtues.

After the Frontline feature aired, the Case Foundation formed PlayPump International and launched a campaign to fund and deliver the pumps to communities in rural Sub-Saharan Africa. Millions of dollars poured in and a host of celebrity backers jumped on the bandwagon.

Reality Check

Reality Check

The PlayPumps were distributed with much fanfare; however, problems quickly emerged. For example, it took much longer to pump water from the ground than by using a conventional pumping system. The pump also obscured a dividing line between what was considered work and what was play, which became problematic. UNICEF reported that "When children are not available, adults (especially women) have no choice but to operate the PlayPump. While some women in South Africa and Mozambique reported that they did not mind rotating the "merry-go-round," in Mozambique they also reported that they got embarrassed where the people watching them did not know the linkage between the "merry-go-round" and the water pumping." (UNICEF report available as a pdf)

At $14,000 per pump, which excluded the price of drilling a borehole, the costs were comparatively higher than other technologies. Wasrag reported that "You could provide at least four conventional wells with hand pumps and associated safe sanitation and hygiene education for the cost of one PlayPump."

By 2010, just three years after the launch of PlayPump International, the organization folded. Daniel Stellar of Columbia's Earth Institute summed up the reasons as a whole-hearted embrace of technology over the more fundamental problem of groundwater supply. "If sufficient supply isn't available to start with, no amount of pumping, no matter how playful it may be, will help," she wrote.

The Climate Change Context

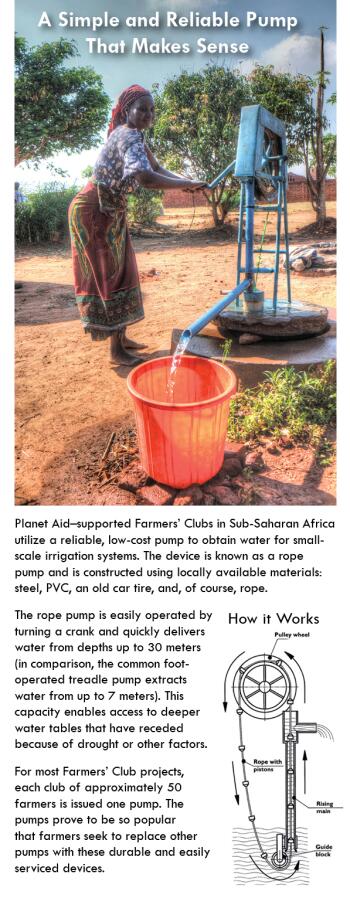

The water crisis facing the African continent has grown increasingly acute. The Guardian recently reported that nearly 60,000 water pumps are being installed per year in sub-Saharan Africa; however, they are continually breaking down and thus rendering a large percentage of wells unusable. The best solutions appear to be the simplest technologies that can be easily repaired using local resources.

The water crisis facing the African continent has grown increasingly acute. The Guardian recently reported that nearly 60,000 water pumps are being installed per year in sub-Saharan Africa; however, they are continually breaking down and thus rendering a large percentage of wells unusable. The best solutions appear to be the simplest technologies that can be easily repaired using local resources.

Such problems are also exacerbated by the accelerating impacts of climate change, which are making groundwater and surface water increasingly scarce. The effects are being felt at every level, and not just in community wells that are drying up. For example, the New York Times reports that the Zambezie River in Zambia has reached such low levels that the Kariba Hydroelectic Dam has been unable to generate sufficient power. The result has been widespread blackouts and a crippling of the country's nascent industries (Zambia had been on the path to progress and was considered a development success story).

Understanding the Throes of Development

As illustrated by the PlayPump example, understanding the local context of a development initiative is vital, as is monitoring progress and learning from one's mistakes. Conversely, it is also important not to rush to judgment when results are fitful or when setbacks occur.

Getting "pumped" for a quick development fix will only lead to disappointment. Development requires time and effort (lots of it) and ample reserves of patience and perseverance. Moreover, in today's worsening climate context, progress is even more difficult and elusive. Those involved in international development over the years have learned its hard lessons. As Jean Case writes, "Turns out innovating is hard work anywhere and anytime. In the developing world even more so."